It is not uncommon for a great spiritual personality to be born in poverty in remote villages out in the country and to emerge from it gradually into the wider scope of the world at large. In any case, whether such circumstances and nearness to nature deflects such minds to the investigation of life and its meaning, is of no ultimate significance, for a great personality is something more than just the circumstantial background from which he springs, and natural conditions may leave their impression the character or they may not, as the case may be.

0n Friday 10th of October 1885, in the village of Songpinong, Supanburi province, Sodh Mikaynoi, as he was named, was just another bundle of helpless humanity issuing into the world. Nevertheless, the intelligence and strength of character of this helpless bundle manifested itself even at an early age. One day when he was a year old, Sodh started to cry for some cakes, asking for his mother. The relative, in whose charge he was, tried to comfort him by saying that his mother had gone to work in the fields. At this he suddenly stopped crying. His mother (thought he) had to go to work in the fields. This meant only one thing. That he had been born in a family which was poor. From that day forth he never cried for cakes again.

If Sodh had set his mind to achieve anything he would get down to it and not leave off until it had been accomplished. In his chore of helping his parents on the farm, it so happened that the baffaloes often strayed off to mingle with the buffaloes of the neighbouring folk. Little as he was, he would make off and not return until he had tracked them down, which often enough took him into the dark before he ended the quest, leading them back through the night.

His compassion for animals was great. Another of his chores was to help his folk plough the fields each morn. As it neared eleven o’clock, he would gaze up into the sky to note what time it was. His sister often took him to task for this, accusing him of only waiting for the moment to take time off. However, the old folk knew that this was not in his mind, but rather the old proverb that eleven kills the buffaloes’, which was for him a grievous crime. He worked according to schedule, and no matter what anyone might say, stuck to his belief, of not working the animals after eleven. If he saw that they had been overworked and were terribly tired, he would lead them off for a bath before he let them loose to graze at freedom in the fields.

In this fashion he helped the old folk until the age of nine. His uncle having become a bhikkhu, his mother sent him to study under him at the village temple of Wat Songpinong. In those days, when bhikkhus were the only teachers and there were no public schools, it was customary for a bhikkhu not to take residence in one place for long. Thus, after only a few months his uncle moved to another temple, and he followed. The bhikkhu next moved to a temple in Thonburi, across the river from Bangkok. As this was quite a distance from his native village, the young boy did not follow him, but was dispatched to study at Wat Bangpla in Nakorn Pathom instead.

He was at that time eleven years of age. He remained there for two years, and increased his knowledge of Thai and Khmer. After which he returned to Songpinong. Then, when he turned fourteen, his father died. The responsibility of administering the family business of farming fell on his young shoulders.

The family possessed two river boats manned by a few laborers, whose task was to float the rice-produce down to Bangkok two or three times a month. Young Sodh displayed efficiency in the handling of his charge, and was loved and respected by his employees as a person of strong character and great energy. Once, when the boat was anchored at Bangkok, an employee of his brother-in-law stole a thousand baht. He went to the police and together they pursued the thief by boat all night until dawn. Sodh spied the thief at one of the windows of his house and the officer was informed. However, before the boat could come to shore the thief had hid himself. Noticing that the man left traces with his wet footsteps, he told the police to wait in front while he himself tracked him down. He found the man hiding in the haystacks, who as soon as he saw Sodh coming dived into them. But the police having been informed, he was pulled out and handcuffed. They then retrieved the cash.

Young Sodh supported his family up to the age of nineteen in this way, without misgiving, until a certain incident occurred. As he was returning to Songpinong with an empty boat, after a successful trip to Bangkok, he came to a spot where the river was in full spate. No headway could be made, and to evade its onrush the boat was forced to turn aside into a side canal. This canal was a small one and short, but it had the reputation of being infested with bandits. Those vessels which could pass through this canal without being attacked considered themselves blessed.

As it happened, Sodh’s boat was the only one in sight. Thus, as he turned into this canal, the first intimations of fear began to take posses

sion of him, and as a consequence considered the possibility of making himself scarce. And how? By changing positions with one of his employees, and letting the man steer whilst he went forward. For it was the usual procedure for these bandits to attack the steersman first, it being taken for granted that the steersman was almost always the owner of the boat. If he went forward to the prow he had the opportunity to defend himself and make his escape.

As soon as this idea took possession of him, he loaded his gun with eight bullets and went forward, ordering his employee to steer. During this exchange the boat was floating down into the most secluded part of the canal. It was only then that he began to be plagued with doubt about his project. After all, this man whom he engaged earned only twelve to thirteen baht, whereas he was not only the owner of the boat but the cash as well. Was it fitting, therefore, that he throws the risk of death upon him? It was indeed a bit too much!

These thoughts brought great disgust, even as compassion took its place, for it was only fitting that if anyone was to be slain it was he who should bear the brunt, letting the man escape if he could, for he still had a wife and child to maintain. With this decision, he ordered the man to return, whilst he retired to his former position at the stern, gun in hand.

By that time, however, the boat had drifted on and was approaching the mouth of the canal, where many cargo vessels were anchored, preparatory to crossing down the canal as soon as the waters rose. The vessels were congested that each one could make little headway, and the merchantmen were shouting among themselves. The danger of being attacked, therefore, had passed.

Sodh realized that the moment of crisis had been crossed, and was indeed a boon. This business of earning a living, brooded he, was a heavy load indeed. Bathed in sweat just like his father before him. His father had grown ill on such a trip like this, and as soon as disembarked grew worse, and finally died, and no efforts of his could save him from that. And he took nothing with him, his body just died. Not one of them had died with him, he had died alone. That too would be his fate, there was no escape from that. Always looking for money, no time to rest. If one did not hurry up and earn, one was considered a low fellow, without respect in the community. Whenever one associated with others one was ashamed of one’s poverty. It was so from of old. His forefathers had lived like this, countless of them, down to his father and himself. And where had all of them gone to now? Dead, even as his father. And what of himself? Also, the same thing would happen without anything to show for it.

Brooding in this way after the strain of his escape, made him grow cold. Until he got so depressed that he lay down in the back and made believe that he was dead. That his ghost was wandering about seeking for his dead forbears and those friends he had loved. But they couldn’t see him. And why? Because he was a ghost. So he threw clods of earth and sticks at them. But they thought that a ghost from the forest had come. And why? Because they couldn’t see him. Drifting on seeking this one and that, but no one could see and take notice…

He forgot himself dreaming in this style. As Soon as he got to his senses, he hurriedly lit incense-sticks. And made a vow: Let me not die. Let me become a monk. Once a monk let me not disrobe. Let me be a monk all my life…

These thoughts were found written amongst his papers.

The responsibility of supporting his family, however, rested on his young shoulders. It was not until three years later, when he was twenty-two, therefore, that he had the opportunity of entering monastery.

In May of that year, after having loaded the boats with the rice harvest bound for Bangkok, he appointed one of the employees to take charge, while he himself made his way to Songpinong temple to prepare himself for ordination.

The second day after his ordination, he got down to the task of studying the Pali scriptures. He memorized the mantras and the Patimokkha. However, while memorizing the scriptures he came to ‘avijja paccaya’, and wanted to know exactly what this meant. But he could get no explanation from his fellow bhikkhus. Even his teacher could not explain, saying instead:

“Good man, they never translate these things, you know, they just recite them. If you wish to know what it is you must go to Bangkok…”

He returned to his cell, thinking the bhikkhus in this temple are stupid indeed. They can memorize and recite but know not what it is all about. What then is the use of memorizing anything? This is the door to stupidity, not knowing how much there is.

It was thus that he decided to head for Bangkok.

After only seven months in Songpinong temple, therefore, he went to his mother to request for permission to proceed to the capital. She was far from anxious to do so, but he persuaded her in the end, although she agreed with only half a heart. He asked for requisites for the trip, and resolved never to do so again.

He left Songpinong village and made straight for the temple of Wat Bodhi in Bangkok. Taking residence there, he was eager to learn all there was to know. Astrology, occult lore, even alchemy were in fashion, and he experimented with them all, since there was nothing to lose. He did not depreciate others’ knowledge as not genuine, on the contrary recognized that there was some truth in it. But he was dissatisfied. Finally, he abandoned them, giving away his books on the subjects, and devoted himself to Vipassana.

He had brought along a younger brother of his from Songpinong to study and practice. But in his fourth year as a bhikkhu, Candassaro as he was then called, fell ill and was removed to another temple to be attended to, his brother going with him.

He had a vision. A man appeared and offered him a bowl of sand. He took a pinch. When his brother was offered some, the boy took two handfuls. A few days after this vision the boy grew seriously ill. He himself suffered an attack. However, as soon as his illness died down, he took his brother hurriedly back to Songpinong for a cure. But the boy of eighteen did not recover, and died.

After the cremation, he returned to Wat Bodhi.

During his stay here many obstacles had to be overcome. On his early morning rounds for alms, as is a bhikkhus custom, he received insufficient food, sometimes not at all. Once he received only an orange.

The first day of his stay there he received nothing at all. The second day it was the same. Wherewith the thought perplexed him whether one who keep the 227 rules of morality is to perish for lack of something substantial to eat. If so, then perish he would. Because if he failed to receive any rice at all he refused to eat. Better to starve, for if he died all the bhikkhus in the city would have enough to eat. And why? Because the layfolk hearing of the news that a bhikkhu had perished of starvation, would soon feel heartily ashamed of themselves, and out of compassion feed them all.

On the third day at dawn he went out again. After walking for a long time he received only a ladleful of rice and one banana. It was rather late when he returned to his cell, weary after his walk and the empty stomach of two days grace. Without much delay, therefore, he set down to dispose of the meal, discriminating on the food as nourishment for the preservation of life. With his hand on the bowl, he disposed of a mouthful.

Hardly had he done so, however, when he happened to glance up, and saw a dog dragging its steps in the courtyard. Compassion getting the better of hunger, he mashed up the remaining portion of rice into a ball and gave it to the dog, together with half the banana.

Before parting with the food, however, he made an earnest wish. That starvation such as this never cross his path again. Only then did he part with the meal. Although the dog was emaciated and had probably never eaten anything for days, it ate only the rice and left the banana untouched.

Somewhat dismayed at this, he thought of retrieving the banana, but recalled that a bhikkhu does not take back something which he had already given away; it was not fitting therefore to do so. Unless, of course, someone was to re-offer it, with both hands, as is the rule. But at that time and place no such personage presented himself to oblige.

From that day forth, however, he receive sufficient food. Enough even to share with his fellow bhikkhus. Besides this, some layfolk offered to provide him with a tiffin-set of food every day from that day forth.

Nevertheless, as a result of this lesson, Candassaro vowed that as soon as it was in his means to do so, he would establish a kitchen whereby food could be distributed to the monks and novices, without encountering such stringency, saying them all a waste of time going the round for alms when they could devote themselves to study instead.

This was fulfilled much later, after he became Abbot of Wat Paknam, where he established a kitchen and refectory at a cost of 360,000 baht, feeding monks, novices, upasakas, and upasikas of about 900 strong. The upasikas were detailed to run the kitchen. In the beginning, rice had to be shipped from the family farm in Songpinong. Later, however, help came from layfolk and continues down to this day.

In this respect, he was the first bhikkhu of this sort to achieve such a project, fulfilling his old vow. There is this anecdote to throw into focus his ability as a provider of food.

Once, the rice supply in the store had reached its dregs, and there seemed no prospect of a fresh supply for the meal next day. The bhikkhu-in-charge of the store was at his wits end, and went to inform the Abbot. He was told not to worry and to be calm, there would be rice. The bhikkhu, however, had his doubts and returned to his cell to brood on the problem.

That evening, boats filled to the brim with rice came to anchor right in front to the Wat, and sackfuls of rice were unloaded and carried to the store, filling it up, to the amazement of those in charge.

But this was years later. At Wat Bodhi he continued his studies, and did translations of the scriptures. But he did not finish his course. He failed in his examination, and did not continue. He later recalled, that if he had passed it and attained to a high degree of scholarship, the Sangha authorities would have recruited him to work along those lines, to the loss of Vipassana. As it was, whenever he could find time off from the Pali courses, he was practicing Vipassana at this centre or that.

At one of these centres (the fifth he visited), he managed to perceive a bright and lucent sphere, the size of the yoke of an egg, perceived right in the centre of the diaphragm. Which showed that his teacher’s method bore results. His teacher testified to his attainment and elected him to teach.

But he was dissatisfied. If he himself knew only this, was he in the position to teach? He, therefore, taught no one. He also abandoned his Pali course.

Considering that it was about time that he become a wandering bhikkhu, he requested his aunt for a forest umbrella under which to sleep, and refused to take one from any one else, wishing her to receive the merit arising from the gift, due to her past services rendered him.

He left for the provinces, returned after a short period, and gave away the umbrella to another bhikkhu. Later, he made a second trip, and got another umbrella from the same aunt. He walked as far as his native village and took up residence in the ruins of an abandoned temple there. As he was there he saw village boys letting buffaloes stray into the temple precincts, and warned them to refrain, because of the sacrilege incurred in stamping over sacred ground. They, however, refused to heed. He therefore told them to dig up the place, and they discovered numerous Buddha images. Which brought him into great respect.

He, however, returned to Wat Bodhi.

By now he had been in the monkshood for eleven years. He had stopped his Pali course because he had already attained proficiency in the translation of the scriptures, and was satisfied. As for Pali, there was no end to the translation of it. It was enough that he could read and understand. He had fulfilled his wish which he made in the beginning of his studies at Songpinong temple, to be able to translate the Mahasatipatthana Sutta, which he had been unable to do. Now that he had achieved his aim, it was best to devote all his time to Vipassana.

Looking around him, he considered Wat Bodhi with its wide terraces a fit place for meditation. However, recalling the good services of the Abbot of Wat Bangkuvieng, who had provided him with many scriptures, he thought it only fitting that he take residence in that temple for a while, and discourse to the bhikkhus and layfolk there as part of repaying his debt.

It was thus that he went there to reside.

After the season of rains, he recalled that his real purpose in becoming a bhikkhu was to seek the truth, and to remain a bhikkhu till the end of his days. Now twelve years had elapsed, and that truth, that reality, which Buddha knew, which Buddha beheld, he had failed to attain, neither knew nor saw. It was time indeed to devote himself to meditation once and for all. If he perished in the process, then he perished. At least it was better than dying whilst he had been a layman.

It was thus that on the full moon day of September of that year, he retired to the Uposatha with the purpose of meditation. It was already evening and there was no one around. Before commencing, however, he invoked for aid and light. If not complete insight, at least a little portion of the truth which Buddha had beheld, had known. However, if adversity for the Sasana should result from this, then let this opportunity pass from him. But if it should be beneficial, then let this boon be his, for he would be a witness to it for the rest of his days.

It was only then that he prepared himself to meditate in the regular posture, determined that if once he sat down thus and failed to attain to vision, he would not rise.

At that moment, however, he recalled the ants which were crawling back and forth in the crevices of the stone slabs. Picking up a kerosene bottle, therefore, he wet his finger with it to draw a circle round him and thus prevent the ants from disturbing his meditation. As his finger touched the slabs, he recalled that only a moment ago he had made certain vows and here he was already thinking of the ants. The thought of which made him ashamed, wherewith the bottle was put away.

Once having settled himself down to meditate, he forgot the time, and many hours must have passed, although there was no clock to tell. But although all was still and dark in this lonely place the hours had not passed in vain. For it was during this session that he perceived the truth, the reality, the path his Master before him had trodden.

Nevertheless, this realization was not without disturbing thoughts. For the dhamma was indeed profound. If one wished to penetrate it, one had to sink all perception, memory, thought, and knowledge right down into the diaphragm and stop at just this point. But as soon as stopped, it died. As soon as died, again arose. That was the truth. The truth was centred right at this point. If concentration did not sink exactly to centre here, right into the void of the sphere which appeared, then for certain nothing could be seen, nothing at all.

It was only for a time that these thoughts disturbed him. Apprehensive that what already had been gained would vanish by thinking on it thus, he applied himself again.

After a certain interval, a temple came into his vision. He remembered it at once as Wat Bangpla, the temple in which he had studied long ago when a boy of eleven. At that moment he felt himself already inside that temple. Which made him realize that perhaps in this temple there might be someone ripe for this path.

From that night forth, he delved deeper into this technique of concentration. The deeper he delved, the more profound it became. Thus he continued for more than a month. Until the season of rains had passed.

After receiving the Kathin gifts of robes and requisites, as is the custom, he took his farewell of the Abbot, and proceeded to Wat Bangpla, the temple he had seen in his vision, with the purpose of instructing any bhikkhu anxious to learn.

After four months there, three bhikkhus attained to a degree of insight, together with four layfolk. He then took one of the bhikkhus with him to Wat Songpinong.

At Wat Songpinong one bhikkhu attained to a degree of insight.

After the season of rains, in his thirteenth year as a bhikkhu, he proceeded to Wat Pratusarn, the Abbot of which had ordained him. But his old master was dead. He stayed there for four months and during that time many were the layfolk who came, requesting him to discourse on the dhamma. He did so once, to the great satisfaction of all. Again he was invited to deliver a sermon. But he knew that if he did so the present Abbot would be displeased. So before delivering it, he packed his things ready for departure, delivered the sermon, and then went to the Abbot to take his farewell. He then departed immediately, to avoid unwholesome repercussions, making his excuses that he had already arranged to take some bhikkhus to the capital.

He returned to Songpinong and took four bhikkhus with him to Bangkok to study Pali at Wat Bodhi.

Wat Paknam, of which the Chao Khun later became Abbot, was erected during the period when Ayudhya was capital of Thailand, some five centuries earlier. Forty years ago, when the Chao Khun first arrived there, it was deteriorating in neglect. Discipline among the resident monks and novices was lax, after the decease of its Abbot, and also because of lack of student facilities. Due to this state of things, the Chao Khun was detailed to go there and take over. Thinking at first that he would reside there for only three months and then return, he, however, was ordered to hold fast and warned that unless the earth quaked he had better not return. Which was tantamount to a sentence.

As soon as he took over, he saw to it that the resident monks and novices did not remain idle, but that they either study the scriptures or meditate. By his stern measures he thereafter became unpopular, not only among the bhikkhus, who came from families in the district, but also among the layfolk, who began to spread unwholesome gossip. The layfolk who respected him were in the minority.

The situation deteriorated to such a point that drunks got intoxicated in the temple precincts and misbehaved, even going so far as to think of plunder and murder, as the bhikkhus were meeting in conclave.

Then one night eight men came along with the intention of disposing of the Chao Khun altogether, even as he was in the meditation room. One of the bhikkhus on watch went out in defence. Hearing of the disturbance, the Abbot went out to prevent him, saying:

“We bhikkhus must never fight, nor run. This is the only way to win at all times.”

The ruffians seeing that things were not so good, bashed off into the dark.

These obstacles did not dismay the Abbot, because he considered them to be occasions for the augmenting of merit and parami. Despite the obstacles the teaching spread. And as he divided his time to administering to the affairs of the temple, he continued to delve deeper into Vipassana.

The news of his activities spread to the ears of Somdech Vanarat (the late) who had once been his teacher. One day the Somdech called him to task, saying:

“Don’t be crazy, old fellow! Don’t you know that nowadays there are no more Arahattas in the world? Better come along and help us to administer the Sangha!”

That his old teacher wished him well he knew. But this dhamma was profound, and if one did not perceive its profundity it was only natural to be without faith. Thus he listened in respect. And continued his Vipassana.

This brought him into great disfavor with the Somdech. When the old man fell ill, however, the Chao Khun dispatched some of his disciples to cure him by meditation techniques. It was only then that the Somdech thought it worthwhile enough to read the Chao Khun’s sermons on the ‘Dhammakaya’ meditation, which had been compiled and published by layfolk. In his study of this meditation he was assisted with advice from the Chao Khun himself.

As a result, the Somdech began to believe and in fact became rather keen. So much so that he sent for the authority in charge, and ordered him to prepare the necessary papers for electing the Chao Khun as an ordainer of bhikkhus. To which the authority replied: ‘Sadhu! signifying his good wish.’

Regarding his healing powers, the Chao Khun was always being implored to heal layfolk, who did not have to do anything, not even come in person, but just post a letter stating name, time, date of birth, and the illness, and that was enough. There would be long distance healing by mind. No trouble and no fuss.

When he first came to Wat Paknam, there were only 13 bhikkhus and novices, together with a few nuns. Keen, however, that all should do something, whether it be the study of Pali or Vipassana, the temple was soon established as a seat of learning. Until in 1939 a three storied edifice, 60 metres long and 11 metres in width, costing about 2.5 million baht, was built up as a Pali Institute. Which up to this day about a thousand bhikkhus and samaneras frequent, not only the resident monks and novices but from other temples.

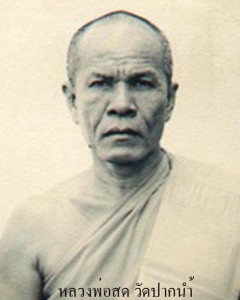

In 1955 the Chao Khun was bestowed the title and ecclesiastical rank of Phra Mongkol Rajmuni, which was later followed by Chao Khun Phra Mongkol Thepmuni.

As the teaching spread, bhikkhus and nuns carried the message out into the provinces. Among the hundred thousands who at sometime or other practiced the method, a few thousands attained the Dhammakaya’s degree of insight.

Parallel to this activity, open to the public at large, the Chao Khun supervised day and night relay meditation teams comprised of bhikkhus devoted to Vipassana research. Another term of nuns, walled off in a separate recess did their own meditation, also in relays, twenty fours, day in and day out. The Chao Khun once in a discourse exhorted the bhikkhus thus: “You bhikkhus, try hard to attain the Dhammakaya in the first place. Then I will teach you for another twenty years, and still there will no end to that which can be learned.”

The personality of a great man has its reflection in the attitude of those who come into his orbit and are influenced by his conduct. It is therefore informative to see him through their eyes, because their close contact preserves details which a distant survey fails to note. Thus, a judge in the high court for thirty-two years, a Pali scholar and a one-time bhikkhu, observes:

“The occasion whereby I came across the Abbot and his teaching was of special significance to me. For at that time Thailand was in the throes of war (1945), with bombs falling out of the skies upon Bangkok and its environs, with the purpose of ousting the Japanese. Because of this I found it wise to retire for the time being and retreated to the suburbs. I took the opportunity at that time of visiting various Wats (temples) so as to increase my knowledge of the Buddha Sasana. I received much fresh and peculiar knowledge in this way.

“However, it struck me as also something strange that when I displayed my desire to get down to active practice of Vipassana and asked for light on this matter, the information I received was not made clear and failed to appease me. It was as though such knowledge was top secret. So it seemed to me when in some temples I saw boxes full of books labeled in Cambodian letters outside ‘Vipassana’. I could make out the lettering because I had studied Cambodian, I wished indeed to know what the boxes held but dared not open them without permission. Receiving no satisfactory reply to my questions I received instead the impression that Vipassana was something to be found only in ancient books, as something antique.

One day as I was seated talking to an old lady, a neighbor of mine, who had also retreated to the suburbs to evade the bombs, a man came along and started talking about how he had once learnt Vipassana from a nun. I pressed for more information on this point, expressing the view that Vipassana was the practice of meditating on dead corpses. The old lady cut in at once, saying that was not Vipassana but only meditation on impermanence. I therefore asked her what Vipassana was. And was told that it was the investigation and perception of the realms of heaven and hell and Nibbana.

“I was confounded. The man who was present was also amazed. Never in my days of learning the written dhamma had I heard it expressed like this before, in such a casual tone. It is true that in the scriptures there was mention of Moggallana Thera and others visiting such places, but there was no mention of that being Vipassana. As for Nibbana, it was beyond thought or speech, as far as I was concerned. Nevertheless, the old lady persisted in her view, saying that she would give me a book to read, concerning the teaching of the Abbot of Wat Paknam.

“However, it was much later that I came across a book dealing with the Abbot’s meditation techniques. Again I was astounded. Especially when at the end of the book it said that there was much more knowledge to be gained, but only for the advanced student. It is needless to say that I was in a dubious mood. However, thinking to myself that no matter how much knowledge one may already possess there was always still more to learn, and to think one already possessed all knowledge was the conceit of a fool. I decided to find out for myself if there was indeed something to be learnt from the meditation methods advised.

“One day I availed myself of the opportunity and visited Wat Paknam. The Abbot was at the eleven o’clock meal, and there were many seated around awaiting his good pleasure. I went forward to make my obeisances, expressing also my desire to learn. He bid me wait awhile and went on with his meal in silence.

“Eventually, opportunity was offered me to come closer and converse. He began to discourse on the virtues of the Buddha explaining as he went each virtue. As I listened I was impressed by the profundity of his exegesis, expressed in a manner which I had never heard before.

“With the memory of this discourse ringing in my ears, I in the days which followed pursued my intention, of getting to know his teaching more in detail. He discoursed on the dhamma on every full moon and quarter days, as well as Sunday. His discourses leant heavily in the direction of concentration practice. Listening in the temple on these days I realized that if the teaching was not recorded it would soon be forgotten, which would be a waste, not to mention tiring him out by constant repetition, I therefore came up with the suggestion that these oral addresses should be recorded. He agreed to my suggestion, and I started to jot down the teaching.

“As far as I know, bhikkhus who practice meditation seldom possess the happy gift of expression. Those who preached well were more often than not scholars of the written word. However, I learnt later that the Abbot was himself once a Pali scholar, and it was due to this early training that he was able to express all dhammas in the light of his broad background. He would announce his subject in Pali and deliver the sermons in relation to concentration practice, interlarding the discourse with a supporting amount of Pali terms. In this way he never expounded at random but always substantiated his meaning from the Pali text. He relied with special emphasis on the Maha Satipatthana Sutta for this.

“The manner in which the Chao Khun regulated his days, was as follows:

Leading the bhikkhus and samaneras twice a day, morning and evening, in paying homage to the Triple Gem in the Uposatha, and ending with a sermon.

Sermons delivered to the public at large on each full moon, quarter moon, and Sundays

Meditation practices both night and day with the bhikkhus, the nuns in a separate section.

Every Thursday at 2 o’clock in the afternoon a meditation class open to the public.

Supervising Pali Institute where qualified teachers taught the scripture.

“Unless absolutely necessary, the Abbot never moved outside the precincts of the Wat, his efforts and time being devoted exclusively to the teaching of meditation. If laymen invited him out to partake of meals at their homes he would evade the invitation by inquiring if another bhikkhu could go in his stead. Nevertheless, he received guests at certain regular hours. Once after the eleven o’clock meal, and again at 5 o’clock in the afternoon. Other than that these times he was usually to be found supervising classes of meditation among the bhikkhus.

“Luang Por (which means father, and was the name by which he was referred to by his disciples) stressed meditation and his teaching leant heavily in the direction of ultimate truth. I have heard him discourse week after week on the various modes of conditionality (paccayas) as found in the Abhidhamma.

“As far as I have observed from close contact, despite the false and unwholesome rumors spread about him, he was free from blemish in all these respects. Besides possessing a broad and profound knowledge of the scriptures, he was a master in discourse, and without an equal in meditation techniques…”

What follows is the account of a layman who after overhearing some remarks of the Chao Khun’s was moved to some heart-searching, ending in his request to be ordained.

“Gathering from rumors and the newspapers that a foreigner was soon to be ordained at Wat Paknam on Visakha day, I hastened to pay my yearly visits there and to be present at the ordination rites. Accompanied by a friend, I went to pay my respects to Luang Por on Visakha’s eve.

“Many guests were present, and as he talked to them I listened with an attentive ear. Some of the anecdotes he told stimulated profound emotions, so that I was often carried away. Others were tinged with sadness, so that I find it difficult to express. One thing, however, which stuck in my mind was his air of melancholy resignation as he spoke of the ordination ceremony to take place next day. Said he:

“Tomorrow, a foreigner is going to be ordained. He has sacrificed his personal happiness, and leaving his people crossed the seas to seek that which is good and true. To speak the truth, we Thai are Buddhists, who pay homage to the Buddha Sasana. Is it not fitting that we should seek some opportunity to live with that which is good and true, and not let the days pass by to our loss?”

“That night as I lay sleepless in the meditation room, his words continued to echo in my ears. That these foreigners came from far off places to seek that which is good and true. We are Buddhists, so close to the Sasana, and should not we be interested enough to go in search, as they, of that which is good and true?

“My thoughts were in bad shape, and as I reflected on my life up to now I knew not on what to stand. What had I, which could serve me as a stay, steadfast and true? Nothing at all. Each day muddled up in work and a household life, always on the go to build up prospects for the future, just each day ahead. It was all right so long as I could use it all. Other than that there was nothing that this worldly life could do for me. If I went on at this rate there would be no end to all the heartache. There would be no escape from the daily round, and leading such a life without meaning I would simply grow old in vain.

Thinking in this somber strain I remembered the saying that those who know the taste of the dhamma even for one day are better than those who know it not, even though they live up to a hundred years. At this turning point in my life this saying seemed only too true. I was going on fifty-nine, and if I didn’t take the opportunity now, then when? I would surely grow old and die in vain.

It was a sleepless night for me. Neither had I a friend in whom to confide to ease my distress, or from whom to receive advice. I had no one but myself. I was my own true friend. But how could I warm or console myself? I brooded over the thought of giving up the household life, full of vexation and pain as it was, without a break. How long was I going to wait? Even a foreigner wished to be ordained. I was much closer to the Sasana, almost like an owner, and could I remain indifferent and fail to receive some solace from it after all.

“The result of these deliberations with myself ended in my decision to leave the household life for good and be ordained. This decision once taken gave me relief, as though a great load had been lifted and pushed away from my mind.

At dawn the next day, Visakha day, I went to Luang Por and expressed my desire, saying: I have been learning this dhamma with you for five to six years now, but still I haven’t attained the Dhammakaya teaching. Now I think I possess sufficient faith and courage to be ordained, so that I may have the opportunity to practice in real earnest once and for all.

“He ordained me, according to my desire, and I began to practice in earnest for the sake of that which is good and true. .”

Here follows the account of a bhikkhu who considers his ordination to be a special one, of honor, unique in this respect.

“You would not think that by looking at his broad face and nose, but failing to notice a wrinkle here or there, that this man was going on for seventy. His penetrating eyes and bearing showed him at once to be one accustomed to command, and one did not fail to gain the impression that although his living was plain, his plane of consciousness was not.

“For all the austerity of his appearance, however, in the depths of his eyes as he put forth both his hands to accept the robes I presented, after I had recited the Pali formula requesting ordination, I looked carefully, and saw compassion.

“This of whom I speak is no other than my venerable initiator, Phra Khun Bhavana-kosol (as his title then was), who began to address me:

“You have now had the faith to present the robes in regular seamed condition, which is the symbol of the Arahatta, as prescribed by the Blessed One, in the middle of this assembly of monks, requesting to become a bhikkhu in the Buddha Sasana, as a sign of your goodwill and wish…”

“He delivered this in a plain clear voice, and as he paused for a little breath, lifted up his eyes for a moment to gaze deeply into mine. Eyes which struck me with its strength. And then continued:

“In an ordination such as this, the first thing of importance is to stimulate faith, belief, keenness, firmness, rooted in the Triple Gem, which is the Buddha, Dhamma, and Sangha. This is so because the Blessed One is the owner of the Sasana and has granted permission that bhikkhus be ordained. It is necessary, therefore, that you as a first step study the virtues of the Blessed One…’

“He paused, and gazed at me with his penetrating eyes, as though to read whether I was in earnest enough to take in all that he said. He continued to expatiate on the qualities of wisdom, purity and compassion of the Buddha, impressing me with emphasis of depth.

“He kept looking at me over and over again, as though he would impress my image in his memory, however, whenever my eyes met his I quickly slanted them aside, unable to take the power of his.

“He continued to dissect on the merit of meeting and entering the Buddha Sasana at all, becoming its heir. I had to shift myself a little to ease my foot, for it was rather numb and I was tired, not having been accustomed to such positions before for so long. But was determined to fulfill my part of the bargain, and bore up. Luang Por seemed to understand my distress and gazed at me with compassion, as he continued.

“A bhikkhu has to understand what kammatthana is, because meditation is the means whereby restlessness may be controlled, is the way whereby samadhi arises and the base for wisdom henceforth.. .’

“He then went off to discourse about the four elements and the 32 constituent parts of the body, which the novice had to scrutinize and regard as unwholesome. He reduced the formula to only five, giving the Pali words, kesa (hair), loma etc., and telling me to repeat them after him by direct order and reverse.

T

hen all was silence. I waited for him to place the yellow scarf around my neck, and order me to retire to robe myself, as is the usual custom. For as far as I had observed from ceremonies of ordination, at this moment this was always the normal procedure. But he did nothing of the sort, instead he coolly went on:

“Do you recall the hair which was shaved off your head before you came here requesting ordination? Did you not take up little in your hand and scrutinize it?

“I replied in the affirmative, but at heart remained perplexed. For I could not comprehend the drift of all these questions. Completely in the dark I, nevertheless, hurried in my mind to anticipate if there was anything he was testing me with. But before I could discover a solution, he continued:

“All right, then close your eyes and place the image of that hair in the centre of your body two finger-breadths above your navel. Sink it down right in the centre there, in the cross-section as of a string strung from right to Ieft and front to back, at the point of intersection there. Do as you are told.

“I did as I was told but my doubts did not decrease. He continued:

“Sink all your thoughts and memory down into the centre there, and observe carefully.

“But all was dark as far as I was concerned. After all, what did he expect me to see with my eyes closed? Waiting to see what was next, I became more dubious with each minute. I was tired already, and if his intention was to try me out then the test had failed, for I saw nothing at all. Nevertheless, he persisted.

“To his question whether I saw anything, I hastily replied in the negative.

“Stop your thoughts, keep them still. Think of your hair, let it arise; see it, right there in the centre. Try and think of it alone. Do so and you will see’.

“I did as I was told. I do not know exactly for how long I struggled with the thoughts which troubled me. And as I struggled for control, I consoled myself with the thought that all this must have some meaning after all, otherwise he would not be wasting all our time.

“Strange indeed, but after a time I did begin to see something. Slowly it arose in the dark of me, a mere blur. Gradually, however, it grew clearer. It became so clear in the end that it was as though I was gazing at it with my eyes open wide. But my eyes were shut. What was it that I saw? The hair which had been shaved off my head. At this I began to grow rather excited, unable to suppress myself.

“I see, I see!”, said I in a trembling voice.

“To his question what it was that I saw, and whether it was hair, I replied at once in the affirmative. At the same time I felt relieved, thinking that all was settled and now I could go out and robe myself. But no, it was not to end as fast as I thought.

Look carefully. That hair which see, in what direction are the ends of it pointing? Which way is the shaven portion pointing? In what manner is the middle portion curved?

I sharpened my sight so as to be able to answer him. And as soon as I saw clearly, I replied. This, thought I, is the end of the matter. But again I was wrong he was commanding me to look on. I obeyed, though not without perplexity. After all, hair was hair, and I had already seen it. What then?

“I sat on trying to do as I was told. To the doubts which arose, I consoled myself with the thought that when he said I would see hair, I saw hair. No doubt, in a moment I would be seeing something else…

“As I sat there for I know not how long, I gradually began to experience strange sensations of bliss. My body was growing lighter and lighter in a peculiar way. Despite the buoyancy of my body, however, the heart of me seemed completely at ease. So at ease, in fact, that I find it difficult to express. The hair which in the beginning I had seen, gradually eased away from my vision, until it vanished and in its place a circle of light gradually appeared, and I felt more at ease than ever.

“At first I saw only a circle of light. Gradually, however, it seemed to condense itself. Then it began to expand. “It was like this for some time, with the circle as large as a gold coin. Radiance, spread out from this circle, and as I gazed on my attention was drawn towards centre. Then I observed that it was really like a clear crystal sphere, in appearance as large as the moon when it floats up in an empty sky. Apprehensive that this vision would disappear, I fixed my gaze thereon. I had lost my sense of weariness in the Iegs, and could not exactly say when and how it had left me.

“Do you see anything else? “, the soft voice of Luang Por came to my ears.

“I see light, a sphere the size of a lime”, returned I.

“All right. That is enough for today. Remember this sphere. Whenever you close your eyes you will see it, whenever your eyes are open you will see it. At no matter what time of the day you will see it. You will always see it. In fact, be careful, and never lose it.

“Having opened my eyes, I saw that he was pleased and satisfied. Said he:

That clear sphere is the beginning. It is the path of the Blessed One whereby he attained Nibbana. It is the only path, the straight path; there is no other path. Remember this. Never let it perish from your sight.

With this, he gradually extracted the yellow scarf from the folded package of robes and placed it round my neck, as I bent down to receive it.

“Go now and robe yourself, and return to receive the Triple Refuge…”

“When I lifted my eyes to the clock on the temple wall, I blinked. To my surprise it was 3.36 p.m. I had been seated there in the centre of this venerable assembly for a complete hour and a half. I half kept the Abbot the bhikkhus, my relatives and friends who had come to share in the merit of my ordination, waiting for all this length of time. I alone had caused all the difficulty and delay Luang Por had gone out of his way to show me how to concentrate, to show me the path whereby the defilements are shed away, to enter the coolness and shade, to the wisdom that is the Buddha Sasana. Was it possible? Had this honor really been bestowed me? It had. For there they were, the old Abbot, the bhikkhu assembly present as witnesses ushering me into the brotherhood, and all those layfolk who were my relatives and friends. And they were tired. But Luang Por had not seemed to trouble himself with it at all. He had ignored his own tiredness, and left those folk in their tiredness, just how one person the way to the happy shade. This was a great privilege, and is it any wonder therefore that I consider my ordination on to be one of honor, a great boon?”